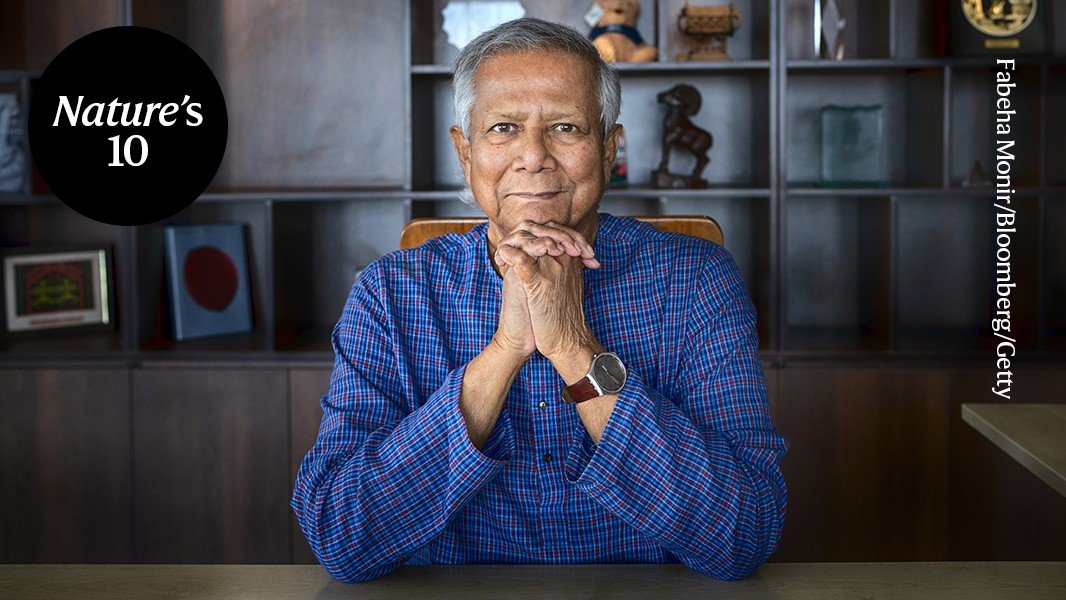

After weeks of deadly demonstrations that toppled Bangladesh’s autocratic government in August, the students who led the revolution had one demand: invite Nobel Peace prizewinning economist Muhammad Yunus to lead the nation.

The task is the greatest challenge of Yunus’s life. In a career spanning six decades, he’s made a name for himself by testing ideas to fight poverty. Using research to inform decisions and understanding systems from first principles is at the core of how Yunus solves problems, say those who know him. “He is in his eighties, but has energy, physical and mental health. He has empathy and is a great communicator,” says Alex Counts, who has worked with Yunus for more than 30 years.

Yunus was born in Chittagong in British-occupied India. His birthplace became part of East Pakistan when India was partitioned in 1947. In the 1960s, he left for the United States and studied under Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, one of the founders of ecological economics, which aims to understand the interplay between economies and the natural world. He returned shortly after East Pakistan became Bangladesh, an independent nation, after the war of liberation against West Pakistan in 1971; he was determined to play his part in building the new country.

Yunus is best known for his innovative approach to microcredit, small loans often of less than US$100. Companies that lend small amounts have a reputation for exploiting the poor by charging exorbitant interest rates. But Yunus showed how small loans can also transform lives for the poorest in society if administered fairly.

As an economist at the University of Chittagong in the mid-1970s, he began testing whether these loans would be repaid and would provide measurable benefits to borrowers. He devised a model in which money was lent to women to improve their businesses. In the first trial, all of the borrowers were able to pay back what they owed. In 1983, he established Grameen Bank, which now provides microloans across Bangladesh. Yunus’s idea lit the spark on what has become a worldwide movement — one that also has its critics.

But there’s a difference between establishing and running an organization such as Grameen, and leading the reform of a country of 170 million people. The question that practically everyone in Bangladesh is asking is whether Yunus can deliver on the students’ demands to end corruption, protect civil rights and provide equal opportunity in employment and education — and secure justice for the families of those killed in the protests.

Before the August revolution, much of the country’s police and civil service and judicial system, along with many universities and even banks had become extensions of the ruling party, says Mushfiq Mobarak, an economist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Yunus and the students — a few of whom are in the interim cabinet — have set up expert working groups to ensure that public institutions are protected from political interference, whichever party is in power.

But institutional reform doesn’t happen quickly, says Fouzia Sultana, research director at the Bangladesh Academy of Rural Development in Comilla. “It’s a complex and gradual process.” Another tension is that some want to see change happen quickly, whereas others don’t think it appropriate for unelected technocrats such as Yunus to propose sweeping reforms while essentially in a ‘caretaker’ role.

The success of Yunus’s tenure as interim leader will depend, in large part, on the student protesters who helped to bring him to power. They are a powerful constituency, with a role similar to that of the young people who rose up against the authoritarian regimes of the Middle East during the Arab Spring that began in 2010. Those uprisings were violently suppressed, kicking off a wave of instability in the region and globally. So far, the story has been different in Bangladesh; both the military and Yunus are backing the students. But that places a large weight of expectation on one man to protect rights and deliver the opportunities that many of the students’ friends and colleagues did not live to see. “We want to read. We want to write. We want to sit exams and do research,” said Prapti Taposhi, an economics student at Jahangirnagar University in Dhaka, during a seminar at Yale in September. “The state needs to do its job.”