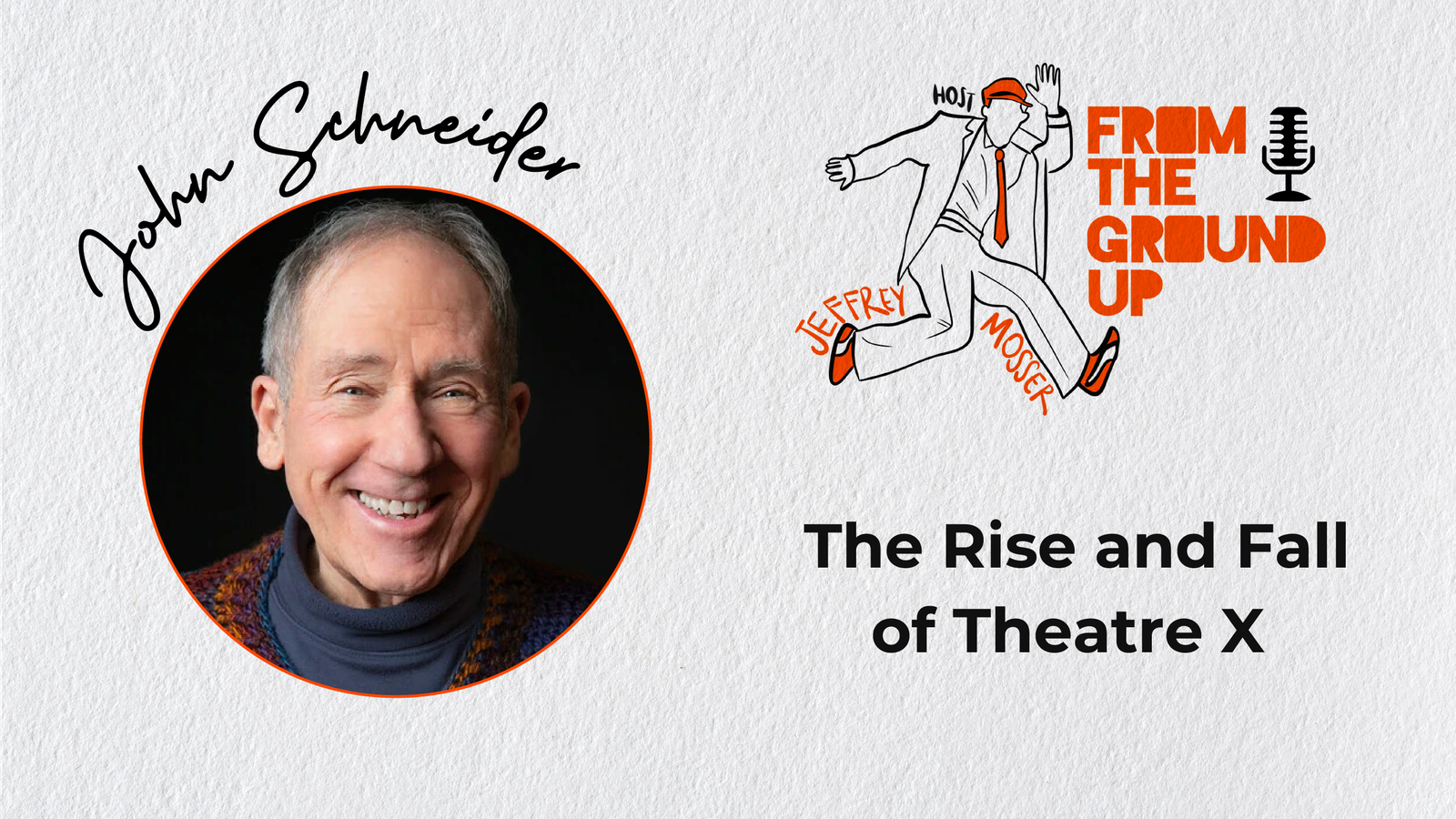

Jeffrey: Are we looking at like 1981, 2, 3 here?

John: Yeah. First of all, let’s go back to the story here. In 1980, the guy from the Yellow Cab company closed down the Yellow Cab company, closed his business, sold the warehouse. The person who bought the warehouse wanted us to pay what it was really worth in terms of rent, which we couldn’t do. One of our members who was functioning as a sort of business manager, this is another story, was involved with a couple of artists in town and the public school system trying to come up with a way for several small arts groups. We were still the only theatre company in Milwaukee, professional theatre company if you can call us that. We made our living that way. That was our life.

The Milwaukee Repertory Theater and Theatre X were the two theatres, but other small arts groups, how we could have a relationship with the school system that would be of benefit to the students in Milwaukee public schools, particularly high school students, and could use what was now on the east side an empty former Milwaukee Public high school, Lincoln High School. And it became then known as Lincoln School of the Arts, and they did bring some students back into it. They were. But first of all, they just gave us space. They gave us the gymnasium, but in case they might want to have the gymnasium back for students, we had to build our own floor over the gym floor so as not to hurt the gym floor. We built walls, we built a theatre inside the gymnasium, but it was extremely workable. And the audience came in through the school and down the stairs and we got it rent-free.

And in return we did workshops with students and visited classes and had students come to see our work. Amsterdam then led to further touring to Germany to Sweden where we were a couple times. We had a long time in Stockholm working, making an original play from scratch with a Swedish company like Theatre X in Stockholm. Toured Great Britain. That was in 1985. The British Arts Council had us tour Great Britain with the second to play off the trilogy. And so that. I think it was 1983 or we were hardly ever in Milwaukee. And our board, including Curtis Carter was looking for a way for us to have another theatre.

And this warehouse in the Third Ward. The Third Ward was on the verge of becoming a combat zone. There were a couple gay bars and not much else there. At night there was, aside from a couple of gay bars, sort of nothing else, dark streets, old warehouses, there was actually a shooting in one of the gay bars, one of the popular gay bars about a year before this and somebody was shot and that put an end to that club. And so that six story warehouse sat empty. Our board members managed to put together a group of investors who, again, because we were a nonprofit organization, got large tax credits so that we actually became owners officially of floors one and floors two of the warehouse.

And then each of the four investors had one of the top four floors that they could put their business in, do whatever they want. That sort of changeover was in 1984, and then we moved in 1985. We had to get special permission from the city because it didn’t meet any building codes for a theatre. We needed several hundred thousand dollars to rebuild it so that it would meet all of those building codes.

The city kept granting us permission to use it until finally they wouldn’t anymore. One of the members of our board of directors resigned as a board member. He was the president, actually, and bought it for the cost of bringing it up to code. And he became the owner of those floors, and we had to pay him rent, so that was hard. But he was still a friend. He then, and the other investors, sold it to another member of our board whose name was Colin Cabot of the blue blood Cabot family, sort of renegade member of that family who had moved to Milwaukee and taken over artistic directorship of the Skylight Music Theater.

And there was an empty lot beside our six-story warehouse. And the Skylight Music Theatre, which was even older than Theatre X, was in the basement, in a shoddy little place. And Colin said, “no, no, no, I want a theatre.” Colin decided to build the Cabot Theater attached to our warehouse, one of the most beautiful theatres in the city, and he raised the money to do that. And the Skylight bought our warehouse and became our landlords, and another theatre moved in, The Milwaukee Chamber Theatre, to help pay for the costs of the whole thing.

Meantime, gentrification had been going on through all of this, and the Third Ward was blossoming and blossoming and blossoming, and the costs, the property taxes went up and up and up and up and up, and the Skylights increased the lease that we had up and up and up and up until we lost the second floor entirely. And we had the first floor, and we had to share that with the Milwaukee Chamber Theatre, who used our small first floor theatre and with the Skylight Theatre, who also wanted to do stuff. And then the Skylight said, well, we can make a lot more money if we rent this theatre out to anybody who wants to use it in town. We can make more money than we’re making off the wonderful lease that we’re charging you to be a resident there. And so you can’t rehearse in it anymore.

You can have a rehearsal space on the second floor and an office on the second floor, but you could only be in there for a week of tech and then for the week of your run, and then you have to get out. I got to say though, that while it was ours, we were also continuing to do what we had done in the Water Street theater and bring theatres from all over the country and from all over the city, music groups, and now increasingly Milwaukee theatre groups and having them pay again for rent-free or 20 percent of the box office or whatever, because it takes a really long time to make an original play. And so for us, it was just keeping the place alive, keeping people coming until we had something ready to present there. But then we had the space to make it in so we could. And it was a flexible black box space until the city said, what? You can’t be rearranging the space like this. You’re breaking building codes.

So they gave us three configurations that we could use. Increasingly, everything’s being pressured in, so now the Skylight is in charge, the rent is going up. It’s becoming increasingly expensive. We’re getting older and older. Members of our longtime company needed more income than we were able to pay, although we were getting it up little by little. We needed a staff, a good business staff that we didn’t have in order to get the kind of grants we needed from the city of Milwaukee, for example. We needed a full-time person who’s doing that, who’s keeping up with, it’s not just writing a grant, but staying in contact with the granting agency to let them know that they’re spending their money well, what you’re doing with it and stuff.

Jeffrey: Did someone from the company just make that part of their job, part of their….

John: Well, initially we had. Initially we did everything and increasingly in order to do any artistic work. And some members of the company then actually joined Equity, which lifted our costs too. Because we had to make a deal with Equity because they could make more money working in equity companies, not even necessarily in Milwaukee, which meant that we had to schedule our work around when they were able to. So it was all money.

In the meantime, our board, which was very distinguished. Another thing that I want to say about Theatre X is that we really led the way on diversifying our organization in every aspect. But this again, was complicated because the original group in the long-time ensemble, we were completely white, and it became very important to us before any other theatre in Milwaukee, I have to say, particularly to put Black people on the stage, but also Latino, Asian people in our cast to involve them in the making of the plays so that they could speak from their hearts about what’s going on in their life.

Anyway, our very hardworking board, very hardworking business people said, look, what we need is to have a national search for a major managing director for this company. And for that to happen, that managing director has to have a say in the artistic decisions that are being made because they will influence what money comes in, what tickets are sold. The hint was already out there that I understood and understand, and that is that Theatre X man, you’ve been doing this for thirty years. Everybody in Milwaukee… Oh, not another Theatre X production, not another play by John Schneider.

And I mean, that idea was around there too. I mean, they liked that we were diversifying, and they liked that they were seeing new faces all the time and new artistic forces coming into… what we were doing. And so they wanted that to expand. And I was very sympathetic to that. I mean, as much as I could be. I actually took a leave of absence when they hired their first managing director because this managing director pulled me aside and said, the board thinks you should back off because it’s John Schneider, John Schneider, John Schneider.

Just sort of see what else we can come up with. I said, right. So I took a job at a, what do you call those things? A temp agency, which actually gave me time to write. And that’s when I started writing about the African-American history of Milwaukee. So when I came back, I had the first of a trilogy of plays about the African-American history of Milwaukee, and then it included the history of Jews in Milwaukee, which also is really interesting and important, persecuted groups in Milwaukee, how they became so important to the fabric of the city. So those are the plays I brought back with me.

Jeffrey: In what year is this temp agency period?

John: Oh, God. The late nineties.

Jeffrey: Late nineties when this managing director, programming started. Okay.

John: Yes. The mid-nineties, it started. Well, this managing director turned out… Welcomed me back. Said, oh, thank God you’re back. He’d been having a really hard time without me. And in fact, the whole company had been so, thank God you’re back. He said, and this show’s another big hit, and people were flocking to them, and we had audiences we hadn’t had before. The one about the history of jazz in Milwaukee, which African-Americans played a big role in it. We turned the theatre, somehow we got permission from the city to let us get rid of a whole part of the seating and turn it into a nightclub and to recreate one of the inner city nightclubs in Milwaukee that was the center of jazz in Milwaukee, and to have great jazz artists performing as part of the show. So they were glad to have me back.

Well, then it turned out that this managing director had been taking the tax bills from the state of Wisconsin and hiding them in a drawer in his desk and not telling anybody. And so suddenly we were faced with a gigantic tax bill to the state of Wisconsin. The board fired that managing director immediately and proceeded to search for a second one. And this kind of blew up the longtime membership of the company. And the board now thought it was really important to keep me around. And the board and this new managing director agreed that now some of these other longtime members who’d been there for a long time should take a leave of absence like I had done and to get more faces up there. And those other members of the board of directors were already very, very angry with the board of directors for even having gotten that first managing director, for believing that they or anybody else could have that big of a say in what was originally a collective, who did everything, was going to do with their professional lives.

I said, but we are now at a level in what we’re doing and in terms of the costs of what we’re doing and in terms of the people that we need to do this, to continue to do this, to have this theatre, whatever it costs that we built that serves us well, and to have this grant money coming in from all these different sources and patrons and all of this history and hardworking board and stuff. And I tried to hold the whole thing together. And eventually it blew up in a pretty nasty way between the board and other members of the company who got a lawyer who tried to argue that the board had no right to do the things that it was doing. And of course, the board had every right, because they’re the people who would have to pay that tax bill, for example, who are the board of directors.

The community board is ultimately responsible. So maybe that’s not the way to go if you want to be an independent collective theatre, maybe you can’t become in the course of thirty-some years such a part of your community with such expenses, with such costs. We couldn’t make by touring anymore because the touring didn’t exist like that anymore. And nobody was touring like that anymore. And so that began a war between a few of the company members and the board. And I tried to hold it all together and keep it going. And Flora Coker stayed with me and tried to do that too. And we hung on for another year, pretty ugly year in town in which everybody in the theatre in the city, which by that point no small thanks to us, was now a pretty large group. In fact, a remarkably large number of theatres in Milwaukee for a city of our size in the country.

And it’s really important that people know that, that people increasingly recognize Milwaukee as a center for the arts in the United States of America, which it is in terms of the quality of what it does here and the amount of what it does here. And it’s also important that the city of Milwaukee recognize that. And we were very, very important on both of those fronts. Our board just said, finally, this is too hard. Let’s call it quits. And it was very hard for the board president to meet with me and Flora and say, our board has decided to leave.

And by that time, these other members of the company weren’t speaking to me anymore or to Flora because they thought we had sided with the enemy, I’m sorry to say, and that I have never gotten over that. That’s a source of pain to me twenty years later, and I hope that someday there’s a remedy for that. And I see that it moves, that we make little steps in that direction. And that’s how Theatre X sunset it. The board said, we’re going to close it down. And they did. So ultimately, you could say it was money that killed an important—not just in Milwaukee or even in the country according to that book, or even in the world—collective ensemble, alternative theatre. It was the cost of operating one.

Jeffrey: Through everything you said, John, I was just constantly noting how things just eroded. This kept coming away. The city took this away, the board took this away, this control was taken away, this financial aspect was taken away. And that’s kind of the heartbreaking thing. Now with perspective, we can maybe think that, but in the moment, it feels like every decision’s made for the right reason in the moment, right?

John: Well, that’s the source of the pain that I feel about the breakup with a couple company members. Because we had always said, oh, okay, so now what do we do? And I understand this, that anger that continues to some degree, I’m sorry to say, from the point of those other people toward me was because they said, well, okay, so let’s go back to the living room.

Let’s go back to making a play in the basement. Let’s go back to how we started the ensemble company we once were, making plays from scratch with whatever we could find. We’ll find grant money, we’ll find people to help us. We have a good reputation as artists. And I don’t know that I shouldn’t have said, yes, let’s do that. But at the time, I felt like, oh God, I can’t.

Jeffrey: Because as you said, as you age, you have other financial responsibilities and you need a certain income. And if you go back to the way you were working twenty, twenty-five years ago of like, yeah, we can do this with our van—

John: We’d given up everything,

Jeffrey: Right?

John: Except our history.

Jeffrey: Yeah. So I can hear in all of that a lot of financial and social conflict in there. Certainly.

John: There are other Milwaukee groups I know that have had similar problems with their boards that have hurt them and closed them down, but it does center around money. It does center around the fact that to be a nonprofit professional group, you need a board of directors, a community board of directors, and by law, they are responsible financially to the organization. And so they have to take that seriously.

Jeffrey: Can I go back just for a second to how did you develop the board of directors, and then a board of directors has to be on board with your vision. They have to really love what you do. And it sounds like to begin with, they provided this space for you and did such lovely work and effort for you. And then somewhere along the line there, it sounds like financial support or something else overtook the other obligations. How did that board develop or change or change their focus throughout?

John: A little fun part is that the first member of our board of directors who was not a company member—the company and the board were the same people initially—in our nonprofit was Sarah O’Connor, who was the managing director of the Milwaukee Repertory Theater, and very much helped build it to the building it’s got today and the company that it is today, and who wanted to help us. In fact, her son did tech work for us. He was our lighting guy for quite a while.

Jeffrey: Oh, cool.

John: Her young son. And she helped us begin to get grants and stuff. That was really great. And then the second member of our board was a woman of some wealth who had moved here from New York City and who loved the off-off-Broadway movement in New York City, and was very excited that there was anything like that here in Milwaukee that you could come to. And of course, they loved what we did and they didn’t want us to change. We got, early board members were people on the city council, for example, who thought it was important for the city of Milwaukee to have this.

They were, as you say, people who wanted us to do exactly what we were doing. It was only as the expenses, I guess, grew as we needed a couple people in the office, not just a business manager, but a publicity marketing development person, a grant person, a little bit bigger company, even to share the artistic responsibilities. That it just came with board expansion, I think. I don’t think anybody joins board because they wanted Theatre X to be something different, but when they saw that it cost more, we needed more money, and they were trying to figure out how to raise that money since they were responsible for it, I think that’s when they began to push.

That’s, I think, when the idea of you have to do in addition to what you’re doing, other things, more kinds of things. And because as I said, you can’t just crank out a next original ensemble based project while we were bringing other people in… Most people we were bringing in, as I said, we’re getting the money for that, and we couldn’t invite people to use our space and then take all the money that they were making.

That wouldn’t make any sense. So ultimately, it keeps coming back to money, and the board did get bigger and bigger and bigger. It did. More board members invited more board members to join, which meant, in a sense, training the board toward what we did. But it also meant the board having more ideas about what Theatre X might do that would excite more people to come and more people to want to give money. And I, in the end, was the only board member who was attending board meetings because other the people were so angry with the board that they wouldn’t set foot in the boardroom for the meetings.

So there was a war going on and there were unfortunate things that happened in that respect too, personal fights between board members and company members that I’m not even sure ever the people who were involved even knew the consequences on both sides… Since I was on both sides, I would hear the consequences of those fights, and I’m not sure that people involved in them even knew how much they mattered.

Jeffrey: It’s just interesting to me how it does take a lot of time to create ensemble-based work. And as soon as we try to put ensemble based work in a world that is like a quote-on-quote traditional theatre process, Milwaukee Rap or Chamber Theater presently or otherwise, the finances of it are so much more crucial. And maybe in that moment, what we don’t realize is it takes a long time to create ensemble-based work. It also takes a long time to write a grant. It takes a long time to write the script that you’ve got. It takes a long time to cultivate the relationships. Right?

John: Exactly.

Jeffrey: So that human power, there’s a limit to actual human life and capacity to be in those rooms and be talking to the right people and be writing the right things for the right monies and all of those things.

John: Playwriting is rewriting. I tell my playwriting students. But the point you just made is excellent. The board members, as they came in, what they had in their own minds is the repertory theatre model. That’s what they understood theatre operation to be. And so that’s what they were trying to, without understanding, as you say, of the amount of time that it takes to do any aspect of that. Without understanding that at all, and without having any other idea of how to operate a theatre. So they kept pushing Theatre X in those directions. Yes.

Jeffrey: A big sigh from the both of us.

John: And I don’t know what the solution is except to stay poor and be your own board or have another job to support yourself. Be a starving artist all your life, which is what I am again, and pushing seventy-five.

Jeffrey: Yeah. Yeah. Oh my gosh. John, thank you for bringing us from beginning to end there in such a succinct way, but that encapsulated so much. I want to go back to you bringing in other theatres a little bit. So in your second space that you were in, your six-story warehouse that you were in, you said you were bringing in acts in theatres and performances from all over the place. How did Theatre X or folks from, or yourself, how did you find folks to bring into that space who might’ve been touring or looking for a place to tour in Milwaukee here?

John: Word got around, I guess. SITI played in the original space, by the way. Yeah. Word got around, I mean, we were friends with Mabou Mines, for example, and the Wooster Group …. Everybody sort of knew everybody. David Herskovits, what’s the name of his theatre in New York? He’s still running it….

Jeffrey: David Herskovits. I’m trying to wrap my brain around that right now.

John: Yeah, I know. I am too. And he was just in the New York Times. He just opened a new piece, an adaptation of something. He was here. He brought something here because he was a friend of a friend and heard about it. And yeah, we didn’t send out messages—do you want to come and play in our theatre? It just became possible. Especially in what’s now the Broadway Theatre Center. The warehouse in the Third Ward was mostly local because there was so much possibility for local groups who were eager to use it. Because it was well-equipped, and it still is. It’s the studio theatre of the Broadway Theatre Center. And it’s used by Milwaukee Chamber and other groups, and even occasionally by the Skylight.

Jeffrey: I think we were still talking about in the eighties. And in that same sort of building, you were talking about how touring was starting to dry up, as you said. Can you talk a little bit more about that and what led to that? Or do you have a sense of that?

John: Well, I don’t know where the cart before the horse, where to put it, but there was, in our big touring years in the seventies, as I said, a real excitement on the part of colleges and universities all over the country to bring this kind of theatre in, because it was the cutting edge, to use an old phrase, of what was happening in theatre in America. And because it spoke to a large degree about the issues that the students were grappling with or about to face or currently facing being drafted if you were a man, for example. And then that phase in American history and in the history of theatre in America passed, and the interest of universities and colleges started to shift too, and maybe they didn’t have the money to bring theatre companies in anymore. Maybe they just could bring in speakers or whatever. Or like I say, rock bands, I think is what kind of replaced us in terms of what universities were bringing in as entertainment.

And so it used to be that we would go to these college booking festivals that were in different parts of the country for different regions of the country, where representatives from different colleges would all come and you’d apply to be able to audition personally. And we often got accepted, so we could actually do a little bit of our work for all of these college representatives. And otherwise, you’d have your stuff at a table in a big conference room, and they could walk around and you could talk with them about what you were going to do and what you might do, and they could see photos of your work and stuff.

And so we would book tours that way. And that stopped happening. Those colleges stopped having those things, or at least as far as we knew, they stopped. Maybe it’s because we were spending so much time in Europe that we weren’t paying attention to it anymore or something. But touring also dried up in Europe. The Mickery closed in 1990. It lasted twenty-five years. So that kind of touring that the Mickery put us on wasn’t happening the way that it had been. At least not in those countries of Northern Europe where enough people spoke English that we could perform for them.

Jeffrey: Yeah, I think the arts were under more scrutiny too, right?

John: Oh my God, yes. Thank you for bringing that up.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

John: Oh, yeah. What’s his name?

Jeffrey: What are arts dollars going towards if it’s this avant-garde trite, right?

John: The NEA Four who had their grants taken away, three of them being LGBTQ performers and the fourth one taking her clothes off. Yes, absolutely. They tried to shut down the NEA completely. The Republicans in Congress. That was the beginnings of the Tea Party. Yes, that was very painful. And that hurt us, by the way, because we depended a lot on our National Endowment for the Arts grant, which shrunk after that happened. I worked for the National Endowment for the Arts for a long time too. Theatre X got excellent reviews when we were writing grants. And so I was invited to be a site reporter and a screener for the playwrights, and eventually I was on the playwriting panel.

And any and all the independent artist panels were completely obliterated. Only institutions were able to apply for grants from the NEA. And no longer could you apply as a playwright, for example, or a composer. And one of the reasons was because nonprofit institutions have community boards of directors who are supposed to control your institution to make sure you don’t strip on stage and stuff or do anything that will offend community standards, which is what the Supreme Court in 1990, I think, decided was the determining factor. Each community could set its own standards of decency, and anybody who broke them was subject to fine or imprisonment or whatever the community wanted to do to them.

Jeffrey: Oh, sounds like a time to bring in a managing director.

John: Yeah. There we go. There we go. Thank you for pulling that thread in.

Jeffrey: That’s what we’re here to do, John, putting it all together, tying this quilt together.

John: Oh, great. I hope people who are listening to this are recognizing and it’s helping make more sense of their lives.

Jeffrey: I hope so too. I think we’re all in context. So many ensembles in the seventies, and the genesis of Theatre X was that you were creating because there were social issues that needed to be talked about, and a draft and Vietnam, and there are waves of these social justice sort of theatremaking in the form of ensemble or collective. And it might’ve been like San Francisco Mime Troupe and whatnot.

John: That was another big influence. Yes.

Jeffrey: And then we go into and then we lean into, and then we’re coming into this period that we’re talking about, the seventies and whatnot. And then companies in the nineties, I mean, we could talk about how many waves or where the waves are, but I think it’s really fascinating because it feels like whenever there’s a big cultural touch point, there’s the inspiration for a new means of theatremaking. And I think that’s really fascinating that Theatre X sort of rose out of that with a social justice aspect or improv around an issue.

John: Because our lives were deeply involved with that stuff. Civil Rights and LGBTQ and women’s rights and Vietnam, of course, which was the worst of what was happening at that time in our lives.

Jeffrey: And that was all improvised to start with. And did you continue improv?

John: Yeah. The improv sessions were whatever they would be. We are Theatre X, we don’t know what we are. Once they committed themselves to making a performance, a way of working developed, which did last for years and years, which was eventually, we called them concerts. Each of us was responsible to come up with some kind of live presentation that we could give to the rest of the group that in some way addressed whatever vaguely and increasingly specifically theme or subject, we decided that we wanted to use as a springboard to whatever was next, and that would certainly give me, as the writer, ideas about what was possible to put on stage because we’d be doing it.

And then the individual ideas that each member individually would bring in, a seed for something. Then we would break, we would all become groups for each of those ideas that the group thought had something going for it, and we would try to develop that as a kind of a group ensemble thing. Again, this is feeding me ultimately as the writer, and then I would go home and I would go for long walks and I would tear my hair out and then I’d write something that was based on that, that might be very true to that or might be really my own inspiration.

And in response to that, I consider myself a playwright, not just a recorder of something. And so that would be my concert, my next contribution to where we were going. But then I had my company try that, respond to that, have ideas about that. Say, oh, I think I really like this. What if this happened or could more happen here or something? And then I could go back and then I could expand on that and I could put new things into that of my own accord. So I was really writing in relation to the ensemble.

It didn’t stay that way all the way to the end, again, because of what was happening to us structurally and so forth, but aspects of it did. And now I got to say too that other members of the company also contributed as playwrights, and we did their work also. We didn’t only do plays that were written by me and they also worked collectively. One of them was Mark Anderson, who’s still in Milwaukee with a company called Theater Gigante, which of all of the existing Milwaukee companies is the closest to something like Theatre X used to be in terms of its international connections and work and its experiments, its purpose. Isabelle Kralj comes from dance theatre and Mark Anderson comes from performance art and a guy named David Schweizer, who’s got a good reputation in New York as a director came and was a member of our company for seven years and directed a lot of stuff.

Jeffrey: It seems that breaking the fourth wall was a theme within your work quite often, and I’m wondering how that maybe came about. That’s a particular field of fascination for me because so much of clown is that, and so much of Boal is that, and so much of that sort of work breaks the fourth wall, and it really exciting to me.

John: The early work, the X Communication, the short pieces were, in style, extremely performative. And so as actors, we often were using clown techniques. We thought of ourselves that way as opposed to Stanislavski-based realism, although we did do that too. It was a mix of styles. We did do some improvisations too that my mind is again jumping all over. So I would say that from the beginning, even from before the first time I saw Theatre X, puppetry was also part of it. They did puppets very early on before I joined, and then repeatedly, for a few times after that, we did puppet stuff. So it’s very geared toward breaking a fourth wall.

It’s very conscious always of the fact that you’re playing for an audience, and I think the radical thing in my life, in that respect, so that I stopped taking it for granted the way that I had was Offending the Audience by Peter Handke, which we staged in an immersive way in our theatre that we could set up however we wanted. So we had immediate face-to-face access with almost every individual in the ninety-nine seat audience. And every time before we would go out, the four of us would hug each other really, really tight because we never knew what would happen, how the audience would react to our provocations and things would happen. Like a woman one time got up out of the audience and started kissing me, put her mouth on my mouth to try to stop me from talking. And our one rule was that we would accept anything that happened, shouting, walking out, jumping up and down, anything that the audience wanted to do in response to us, but we would keep doing the show, whatever it was.

So that, really, I had never been in such a position before and that was a really important play in my life in terms of what is possible to do on stage.

Jeffrey: That series of three plays you talked about, sorry, An Interest in Strangers being the first among them, which, as you mentioned, so Quasimodo and we did that over the pandemic and we did a staging of that, so in 2022, it was my delight to be able to bring that out as a play that we did over Zoom throughout the pandemic. Why I think it worked so well is because it was a commentary on media and here we are inside of a medium of screens and we’re sort of reporting on the reporting and I’m really thrilled that I found that play in the moment that I found it and was like I knew of it and I actually carried your book around. That book of three plays around for a very long time.

John: I know.

Jeffrey: Before I even knew. And then for our audience, yes, we had a coffee a while, much prior to the pandemic, and—

John: You pulled that book out and I couldn’t believe it.

Jeffrey: I will repeat what I think I said to you at that coffee is that there was something when I read through those plays, that there was something that was speaking to the moment that we were in, knowing now that it was a trilogy, this is form and content that resounded with me.

John: Thank you.

Jeffrey: Something resonated. I immediately sensed that the theatre that you were making in that moment was something that I was really excited about and interested in doing, and I desired to make a part of my practice. And so this is a very long preface to saying: what gave rise to putting those plays into a published format? How did that happen?

John: A publisher in Amsterdam, an American actually who had moved to Amsterdam and started a publishing company and saw the, I don’t know, maybe it was just that first one, but I think he saw maybe the second one too, I think, it was after the second one. He became a friend and he was a fan and he said, “Hey, I would really like to publish your…” He must have known about the third one too though, so maybe. Anyway, he said, “I would like to publish your plays.” And did. I don’t know how many, a thousand copies of that book or something, existed. They were available in Milwaukee for a while at the Woodland Pattern, which is the bookstore that began in the lobby of Theatre X’s first theatre on Water Street that we invited to have this small press bookstore.

The third play, Acts of Kindness was done during the pandemic in the first year of the pandemic, I think, at the University of South Wales in Cardiff. And the guy who directed it was on the faculty and had seen us when we toured in 1985 with the second play, and we were in Swansea, Wales. Played at the university there, and he loved it so much that somehow he got a hold of that book and like you, hung onto it, and he did the one on suicide, which really resonated with those students in Wales, in Great Britain, in the pandemic and the financial disasters that came at that time and Boris Johnson.

There were many reasons for those students to feel depressed. And so the possibility of responding to the daily news, and that was the most emotional, I would say, of the three plays. Of course, because it’s about suicide and the characters spoke very, very personally and not ironically, not cynically, not tragicomically about survival or not.

And it has in it a beautiful ancient Greek suicide dance according to a legend in which the women whose men were killed in the Trojan war or something or in some sort of warring thing and who were imprisoned by the Persians or whoever imprisoned the Greeks at that time, quietly commit suicide by dancing on this edge of a cliff.

And one by one, they would move a little closer to the cliff and one by one the line would fall off the cliff and the rest would hold the attention of the captors so that they wouldn’t notice that they were all committing suicide one by one before their eyes. And then those bodies, those of us who danced that dance form, then the shore of a lake and the two central characters who are wrestling with whether to live or die, walk along the shore and stand on the edge of the water and help each other and the central character played by Flora. The last line is she says to him and takes his hand and she says, “do you mind if we just walk on?” See, you might want to do that one someday.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

John: Sorry.

Jeffrey: No, thank you.

John: So I got to talk to the students via Zoom, the students in Wales. And they cared a lot about it, so.

Jeffrey: I feel like we covered the waterfront here. Anything else we didn’t get a chance to say? Anything else?

John: No, except thank you. I love you for doing that play, for keeping my book all these years and for asking me to have this conversation. It’s a part of my life that’s often seems like a dream to me now. And thanks to you, it came alive again. So much so that I wind up in tears.

Jeffrey: Well, John, I mutually appreciate and thank you for your time and sharing your story and your perspective on how things unfolded and whatnot, and gosh, when I first moved to Milwaukee, I had no idea what I was getting myself into and the community that I was finding here and finding my life here and finding you for coffee was such a wonderful beginning to my outlook on how theatre can be made here in Milwaukee, and so it’s really meant a lot to me to have you in my life presently. So thank you so much. It really means a lot.

John: They say the perfect end is to bring it back to what’s happening in the city of Milwaukee, so thank you for that.

Jeffrey: Okay. John, thank you. I love you and I love our time together. Thank you so much. John was one of the first people I met when I moved to Milwaukee because as we mentioned in the conversation, I found a copy of Theatre X’s published play scripts in a Chicago-used bookstore. I bought it because how awesome and rare is it to find a ensemble theatre company with published scripts. Since I met John, I’ve considered him a very important figure and friend. We did a Zoom version of his play Intimacy with Strangers, which was one of the triad he spoke about, and we had a panel discussion afterwards featuring some folks from Theatre X and Philip Arnoult, who was a huge advocate for their work in that period. John mentioned so many things that are echoes of what we’ve heard so far this season, especially from Deb Margolin in episode five from socially-minded work to producing at and within universities.

Their touring company was booked at university theatres because they were doing the cool avant-garde pieces equating to what was a rock show. Very soon this season, we are going to hear from folks at the University Musical Society of Ann Arbor, where they’re in the market of presenting programs of challenging and unapologetic work. This also brings me back to my episode in season three with Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, who has just announced her final show at the time of this outro recording, who talked about the lack of export of American culture and the lack of festival culture in the United States because there is no money for it. But we should also highlight Ritsaert ten Cate’s point of view of how important it is to bring different countries together to bring their points of view to one another. Another tie to Jawole who said that at Jacob’s Pillow, they were taking classes together, they were learning from one another.

That’s what a festival can and should be. Cultural connection. They became a bit of a landlord over the Broadway Theater Center, which is not altogether unique. Often when you hear about theatres sharing spaces, they end up becoming more of a business than an art, but they kept things moving, right. This detail is a bit anecdotal, but I knew someone who ran the Z Space in San Francisco, and they voiced similar frustration of managing the space instead of working in the space. I want to point out here too that there’s a major connection to the board member that buys their warehouse in 1983. It sounds very much like how Theatre de la Jeune Lune lost their space in the early 2000s. Also, I can’t avoid pointing out the similarity they share with Lookingglass Theater Company, where they hired a full-time staff person before they paid themselves as artists. David Catlin mentions this last season as well.

Finally, John mentions how this work fed him as a playwright. The collaborative work made him a better writer. We’re actually going to hear from Jaclyn Backhaus at the end of this season who also was a playwright in a theatre ensemble. That creative part just happens to spark more in the creatives.

Okay, I think we’re starting to see some themes here. Thanks for hanging on to all of those with me, y’all. As I mentioned, these footnotes will be on the episode’s transcript page at howlround.com, so please check it out. And that’s it for me this time. Join me next time as we keep the Milwaukee train going with a conversation with Mark Weinberg from the Center for Applied Theatre. He’s going to steep us in all things Boal, especially how it connects internationally. We’ll be looking at how the core tenets of applied theatre relates to the deeper themes of ensemble-based work. Thanks, artists. We’ll catch you next time on From the Ground Up.

Think you or someone ought to be on the show? Connect with us on Facebook and on Instagram at FTGU_Pod or me at ensemble_ethnographer.

And of course, we always love fan mail at [email protected]. This podcast’s audio bed was created by Kiran Vedula. You can find him on SoundCloud, Bandcamp, and at flutesatdawn.org. From the Ground Up is produced as a contribution to the HowlRound Theatre Commons. You can find more episodes of this show and other HowlRound shows wherever you find podcasts. Be sure to search with word HowlRound and subscribe to receive new episodes.

If you loved this podcast, post a rating and write a review on those platforms. This helps other people find us. You can also find a transcript for this episode along with a lot of other progressive and disruptive content on howlround.com. Have an idea for an exciting podcast, essay, or TV event the theatre community needs to hear? Visit howlround.com and submit your ideas to this digital commons.