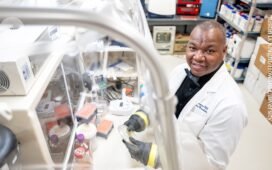

Molecular biologist Natalia Szulc developed the video game DEGRADATOR during her PhD.Credit: Natalia Szulc

From a young age, video games have sparked my creativity and imagination. But a lack of engaging educational games, especially in my native Polish, fuelled a desire to create games that are both fun and informative.

Now, in the fourth and final year of my PhD, I’m studying the cellular mechanisms of protein metabolism. When I’m not doing that, you might find me playing Witcher 3, The Legend of Zelda or Call of Duty. But with a background in biology and computer programming, I saw an opportunity to combine my academic work with a passion for gaming.

Although admittedly an esoteric topic, the regulation of protein degradation is implicated in many diseases, and drugs that exploit it are increasingly entering the clinic. DEGRADATOR is a free, single-player game that introduces players to one of the key components of this process: the ubiquitin–proteasome system. Acting like the cell’s recycling centre, it identifies and breaks down damaged or unwanted proteins so that they can be removed and recycled, helping to maintain cellular health.

NatureTech hub

Players take on the role of an E3 ubiquitin ligase, the enzyme responsible for recognizing and tagging defective proteins for degradation. Their goal: to identify and label target proteins for destruction before time runs out. As players progress, they are introduced to Proteolysis Targeting Chimera (PROTAC) drugs, which exploit the body’s natural mechanisms to remove harmful, disease-causing proteins, such as those involved in cancer.

Quizzes and an in-game encyclopaedia further enhance the learning experience, making complex scientific concepts accessible to a broad audience, including students, educators and people with protein degradation-associated diseases.

Built with a team of six developers, artists and writers, with funding from the Polish Ministry of Education and Science, DEGRADATOR recently took third place in the ‘fully developed games — digital’ category at the 12th International Educational Games Competition at Aarhus University in Denmark. Creating it has been one of the most valuable experiences of my PhD. It allowed me to spread my wings in numerous ways, but if I had to highlight one key takeaway, it would be the perspective I gained from leading a team.

Be flexible

When you lead a project, every decision is your responsibility. For me, that included soliciting and administering funds; hiring and managing a team; and ensuring scientific accuracy — not to mention making countless decisions about game mechanics, user experience, graphics, music, website design and promotional strategy.

At first, juggling these tasks alongside my PhD research was overwhelming. I experimented with different time-management tools and strategies, but none were quite right, especially with a dispersed team working part-time, most of whom didn’t know each other personally. Eventually, I developed my own system that balances tightly planned daily activities with flexible slots for high-priority tasks, whether they were on my to-do list or arose unexpectedly.

I prioritized tasks using the Eisenhower matrix, which bins tasks into four quadrants on the basis of urgency and importance. But this required care: assigning certain tasks as lower priority occasionally led to team members involved in those tasks losing interest. In other words, how I set priorities could directly affect the team’s motivation.

To organize my day, I use Todoist (a to-do list manager) and Structured (a day-planner), which provide a dynamic structure that adapts as the day unfolds. I start each day with a clear plan, knowing which tasks to tackle first, but I also include buffer zones — short time slots I set aside to handle the unexpected. While creating the game, one of my key objectives was to keep the team motivated. So, despite my other commitments, I made myself constantly available to address questions and make decisions quickly, always emphasizing our collaborative effort.

These were the moments when I truly appreciated the flexibility of my task-management system, which kept me adaptable without derailing my whole schedule. Leadership is not just about ticking off tasks; it’s about maintaining fluidity and control amid constant change.

Prepare a contingency plan

As a leader, you often need to make decisions quickly. Sometimes, those decisions will be wrong. To manage the associated risks, I try to anticipate three scenarios with varying levels of negative impact and prepare a contingency plan for each.

For example, when DEGRADATOR was still in development, we were considering attending a key popular-science event. Unsure whether the game would be ready on time, I estimated that, even if progress was 20% slower than planned, we could still finish it on schedule, so I registered us for the event. My three scenarios reflected that uncertainty. In the best case, the game would be completed just before the event but would not yet be fully polished, and we would present its most stable aspects and be transparent about its near-final status. In the intermediate scenario, the game would be ready but contain significant bugs, and we would limit our demonstration to two or three well-tested levels. The worst-case scenario was that the game wouldn’t be ready, forcing us to cancel our participation. To minimize the financial risk, I decided to print promotional material at the last minute, limiting potential losses to the participation fee if we had to cancel.

Anticipate how things might go wrong and plan accordingly, Szulc advises.Credit: Natalia Szulc

Fortunately, the game was completed on time, and we were able to participate. However, the experience helped me to see that decision-making is not just about choosing the right path, it’s about anticipating challenges and taking responsibility for both successes and failures.

Test yourself

Leadership embodies the maxim expressed in a poem by Polish Nobel laureate Wisława Szymborska (Literature, 1996): “We know ourselves only as far as we’ve been tested.” Only by experiencing it can we truly discover how we feel about being in charge and, perhaps more importantly, whether and how our team accepts us as a leader. It is best, therefore, to first take on such a role in a relatively constrained, time-limited project, such as the two years I spent developing DEGRADATOR, rather than discovering further down the line that leadership is not your calling. Although it is fine to step back in such situations, trying out management becomes more difficult when you have long-term commitments and are responsible for others.

Appropriate leadership opportunities for PhD students are rare, but you can find them. Try organizing an international conference or summer school, developing a cross-laboratory educational outreach initiative, initiating a mentorship programme or organizing a hackathon, for instance.

Developing DEGRADATOR provided me with the confidence to take on larger projects and eventually start my own company. Launched in March, LumiRare’s mission is to support people with rare diseases by conducting comprehensive scientific-literature reviews, performing personalized bioinformatics research and connecting people with laboratories and biotechnology companies around the world to guide personalized care and treatment.

I was also incredibly fortunate to have a superb team for DEGRADATOR: Anna Olchowik (programmer), Patrycja Jaszczak (graphic designer), Bartosz Janiak (music composer), Mikołaj Cup and Jakub Tomaszewski (creators of biology lesson concepts for teachers), Michał Taperek (web developer) and Wojciech Pokrzyma (my PhD supervisor and a true mentor). I learnt so much from them, and they made my experience as a team leader truly rewarding.