(RNS) — Harpreet Singh Toor, a Sikh man, is a longtime resident of Richmond Hill, a Queens, New York, neighborhood with a larger than average South Asian population. Toor attends Hindu festivals, works with Hindu men and women and even worships alongside Hindu devotees.

In 2022, when a statue of Mohandas K. Gandhi outside the nearby Shri Tulsi Mandir was defaced and toppled twice in two weeks, Toor was one of the first to appear at the scene to protest the vandalism. “Unless we are united against hate, we can’t eliminate hate,” said Toor at the time. A 27-year-old Sikh, Sukhpal Singh, was arrested in connection with the event and could face 15 years in prison if convicted of the hate crime.

That Queens incident was only the first in a rash of vandalism at Hindu temples over the next three years. At least eight more temples were found desecrated with spray-painted, expletive-loaded messages critical of India and its prime minister, Narendra Modi. In most instances, the spray paint read “Khalistan Zindabad,” or “Long Live Khalistan,” raising alarms in the U.S. Hindu community that a battle going on in India has come to America. So far, no suspects have been found or arrested.

Many believe the attacks were conducted by Sikh separatists who support the idea of an autonomous — and autocratic — state in Punjab, India, the traditional homeland of Sikhi. Every couple of years, a symbolic vote on the creation of Khalistan is held somewhere in Western Sikh communities. Some Hindus say the referendums lead to an increase in temple attacks (including last week’s vandalism on Los Angeles’ largest Hindu temple, which coincided with a referendum planned for March 23 in Los Angeles).

Many ordinary Sikhs, like Toor, who chairs Queens’ Sikh Cultural Society, also say allegations about Khalistan only serve to foment tension between his community and Hindus. A vast majority of Sikhs, Toor pointed out, condemn the vandalism.

If Hindus and Sikhs are not allies, Toor told RNS, it’s because “the government propaganda about these Khalistanis has been so good. They look even at me through that lens, you know, if I can be trusted or not.”

A woman is consoled as people mourn Sikh community leader and temple president Hardeep Singh Nijjar during Antim Darshan, the first part of daylong funeral services for him, in Surrey, British Columbia, June 25, 2023. (Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press via AP, File)

The name of Khalistan has become a source of friction for Hindus and Sikhs in North America due to the June 2023 assassination of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, the Canadian leader of the pro-Khalistan group Sikhs for Justice. Indian state agents were found to be responsible for his murder, as well as another assassination plot targeting Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, another leader of the group, in New York. (India has denied any official connection, most recently requesting U.S. government officials to designate S4J as a terrorist group.)

Many American Sikhs say Modi has become an increasing influence on diaspora Hindus, leading the latter to refuse to acknowledge signs of India’s involvement in the violence. That has fueled contentious debate between some Hindus and Sikhs, whether they are pro-Khalistan or not.

Toor blames this friction on Indian leaders as well. “The government, they have their own vested interest in keeping the pot boiling,” he said.

Recently, said Harinder Singh of the Sikh Research Institute, concerns about repression from India reaching U.S. communities, particularly in the form of surveillance, have forced educational organizations like his own to join the political conversation. Like Toor, Singh believes the idea of Khalistan has been deemed a terrorist movement thanks to Indian propaganda.

Singh sees it instead as an expression of dissatisfaction with the historic treatment of Sikhs and Punjab in India dating back to the 1947 partition. “In every decade, Khalistan has not technically or literally meant a sovereign state,” he said. “It is a word which actually is saying that there are unresolved issues of Sikhs and Punjab. That’s the sentiment people are carrying, whether they are part of referendums or even the ones who don’t participate in it. Basically it’s a display of grievances which are unresolved.

The vandalized entrance sign at Vijay’s Sherawali Temple in Hayward, Calif. (Photo courtesy of Vijay’s Sherawali Temple)

“It is not an illegal issue in India itself,” he added, making clear that to present recent temple vandalisms as “Hindu-Sikh conflict” is inaccurate. “To present it as something so drastic and wrong or bad outside of India, it also doesn’t make sense.”

But to Harjeet Singh, a pro-Khalistani Sikh in Seattle who will travel to L.A. for this year’s referendum, the rising suspicion that Sikh actors have carried out these attacks is “very damaging.”

He cited a March 2023 Hindu temple graffiti attack in Australia, which was blamed on pro-Khalistani elements, but was found by Queensland police to have involved a “Hindu hand.” “It’s just unthinkable for a Sikh,” he said. “And if (a Sikh) ever did it, the Sikhs themselves would take ahold of that guy and give him a punishment he won’t forget.”

Sikhs’ devotion to freedom of religion, theirs or others, “is just core, at the heart, of our being,” Singh said. “We grew up reading the sacrifice of the ninth guru,” he said, referring to Guru Tegh Bahadur, known for giving his life to protect Kashmiri Hindu holy men from forced conversions during the Mughal era.

Sikhs rally near San Francisco City Hall for the California Khalistan Referendum, Sunday, Jan. 28, 2024, in San Francisco. (Photo courtesy Harjeet Singh))

According to Pranay Somayajula, an organizer with the progressive Hindus for Human Rights, the temple vandalism attacks strengthen a “Hindu right” narrative that “conflates any criticism of the Indian government with an anti-Hindu sentiment.” In placing blame on Khalistani actors, said Somayajula, those who support Modi are using a “convenient angle with which to whip up the diaspora into a frenzy.”

Many Hindus may connect the Khalistani cause to the 1985 bombing of Air India flight 182 — the largest terrorist attack in North America before 9/11, in which 329 Canadian, British and Indian citizens were killed. Associates of Babbar Khalsa, a militant Khalistani group, were implicated, but not confirmed responsible for the attack.

The bombing, many believe, was a response to happenings in India at the time. Thousands of Sikhs had been killed or injured in an anti-Sikh militant operation in 1984 at the Golden Temple, a Sikh landmark in Punjab, by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Gandhi was subsequently murdered by two of her Sikh bodyguards. The anti-Sikh riots that followed killed thousands more Sikhs.

Forty years later, said Singh, Hindus in the U.S. will call him a “terrorist” without knowing his views about Khalistan. The Sikh community is not a monolith, he said, and the Khalistan movement is not represented by any one organization, nor is a political stance against India necessarily an anti-Hindu one.

“We have to create this positive narrative around Khalistan and tell people that this is not about hating Hindus, and this is not about creating a theocratic state,” he said. “This is about the freedom of religion, people’s identity, people’s natural resources and their right to self determination, and against the homogenization of the subcontinent. And hopefully, if we create that narrative, I will see some intelligent Hindus coming and aligning with us.”

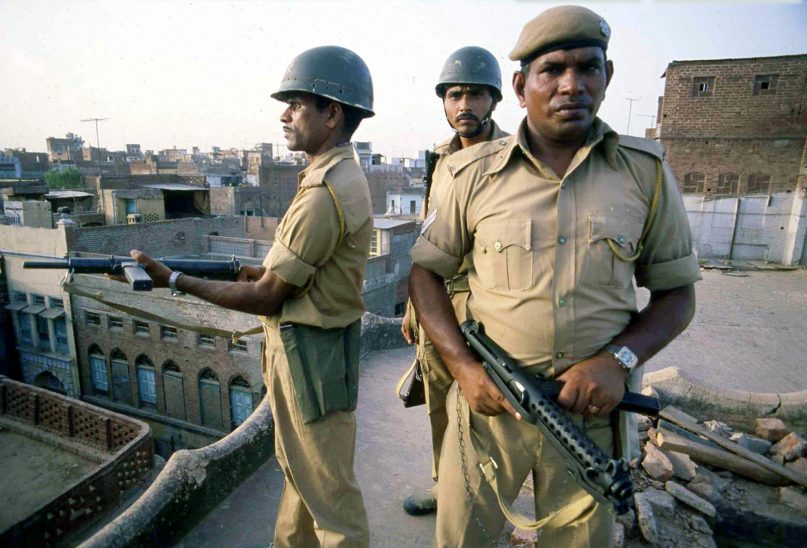

Indian troops take up positions on rooftops around the Golden Temple, in Amritsar, June 6, 1984, after soldiers started to move into the complex. (AP Photo/Sondeep Shanker)

Tarunjit Butalia, an official at the ecumenical organization Religions for Peace USA, said the Golden Temple battles “significantly increased the gulf between the two communities,” despite their previously “amicable and friendly” relationship as Indians.

“Since then, it’s like an open wound that has festered,” he said. “Now we come to the current situation, the distance within the communities and the level of mistrust, I believe, has only built up over time, and each community has stereotypes of the other. These [temple vandalism] incidents, I think, have made it even worse.”

“Defaming” the entire Sikh community for these vandalism incidents, however, is not the answer, said Butalia, and reflects Indian propaganda that portrays Khalistan as a “beating stick” to silence Sikhs. The way forward, he said, is “decoupling” both groups from South Asia.

“I think what is important for Sikhs and Hindus is to come together as Americans,” he said. “We have a complicated history in South Asia. I don’t think we can sort that today or tomorrow, or the next five years or 10 years. But what we can do is come together and talk about, how do we relate to each other and mutually respect each other and our places of worship here in the United States.

What we need to do is simply listen to each other without the need for defending the other’s position. The way to soften each other is to listen to the pain of each other’s communities.”