Chatbots have the potential to sway democratic elections — and the most persuasive methods tend to introduce factual inaccuracies.Credit: Marcus Harrison/Alamy

Artificial-intelligence chatbots can influence voters in major elections — and have a bigger effect on people’s political views than conventional campaigning and advertising.

A study published today in Nature1 found that participants’ preferences in real-world elections swung by up to 15 percentage points after conversing with a chatbot. In a related paper published in Science2, researchers showed that these chatbots’ effectiveness stems from their ability to synthesize a lot of information in a conversational way.

AI is more persuasive than people in online debates

The findings showcase the persuasive power of chatbots, which are used by more than one hundred million users each day, says David Rand, an author of both studies and a cognitive scientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

Both papers found that chatbots influence voter opinions not by using emotional appeals or storytelling, but by flooding the user with information. The more information the chatbots provided, the more persuasive they were — but they were also more likely to produce false statements, the authors found.

This can make AI into “a very dangerous thing”, says Lisa Argyle, a computational social scientist at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. “Instead of people becoming more informed, it’s people becoming more misinformed.” The studies have an “impressive scope”, she adds. “The scale at which they’ve studied everything is so far beyond what’s normally done in social sciences.”

AI influence

The rapid adoption of chatbots since they went mainstream in 2023 has sparked concern over their potential to manipulate public opinion.

To understand how persuasive AI can be when it comes to political beliefs, researchers asked nearly 6,000 participants from three countries — Canada, Poland and the United States — to rate their preferences for specific candidates in their country’s leadership elections that took place over the past year on a 0-to-100 scale.

Influence of Facebook algorithms on political polarization tested

Next, the researchers randomly assigned participants to have a back-and-forth conversation with a chatbot that was designed to support a particular politician. After this dialogue, participants once again rated their opinion on that candidate.

More than 2,300 participants in the United States completed this experiment ahead of the 2024 election between President Donald Trump and former vice-president Kamala Harris. When the candidate the AI chatbot was designed to advocate for differed from the participant’s initial preference, the person’s ratings shifted towards that candidate by two to four points1. Previous research has found that people’s views typically shift by less than one point after viewing conventional political adverts3.

This effect was much more pronounced for participants in Canada and Poland, who completed the experiment before their countries’ elections earlier this year: their preferences towards the candidates shifted by an average of about ten points after talking to the chatbot. Rand says he was “totally flabbergasted” by the size of this effect. He adds that the chatbots’ influence might have been weaker in the United States because of the politically polarized environment, in which people already have strong assumptions and feelings towards the candidates.

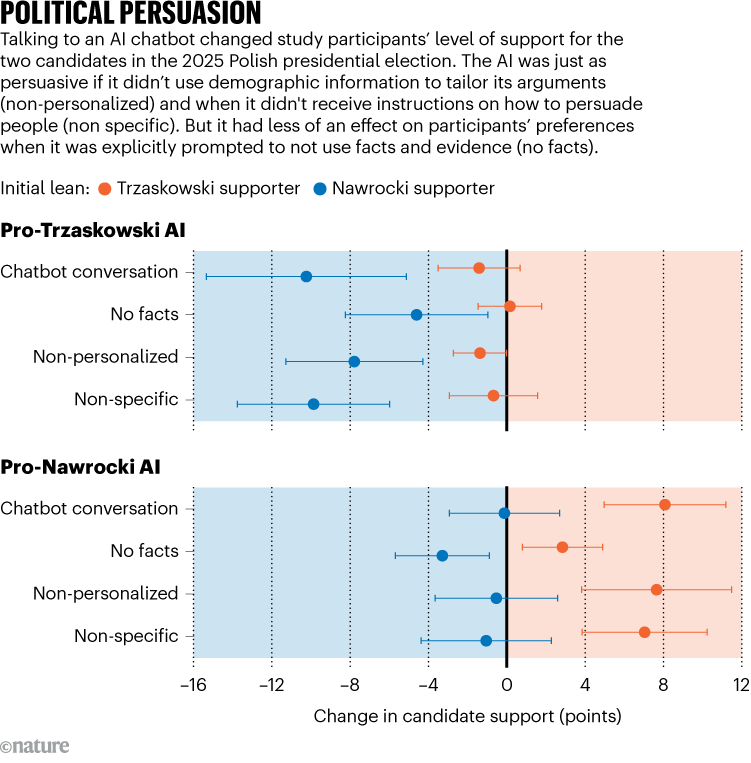

Source: Ref. 1

In all countries, the chatbots that focused on candidates’ policies were more persuasive than those that concentrated on personalities. Participants seemed to be most swayed when the chatbot presented evidence and facts. For Polish voters, prompting the chatbot to not present facts caused its persuasive power to collapse by 78% (see ‘Political persuasion’).

Across all three countries, the AI models advocating for candidates on the political right consistently delivered more inaccurate claims than the ones supporting left-leaning candidates. Rand says this finding makes sense because “the model is absorbing the internet and using that as source of its claims”, and previous research4 suggests that “social media users on the right share more inaccurate information than social media users on the left”.