How SpaceX Will Turn a Workhorse Vehicle into a Hulking Destroyer of Space Stations

SpaceX will supercharge its Dragon capsule to send the International Space Station to a watery retirement

In just a handful of years, a beefed-up version of SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft will launch on a unique mission to safely destroy the International Space Station (ISS).

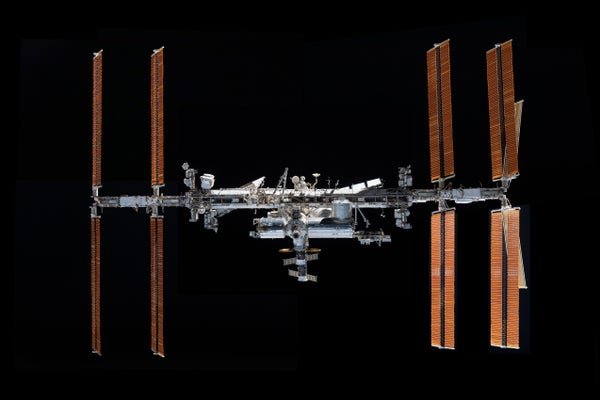

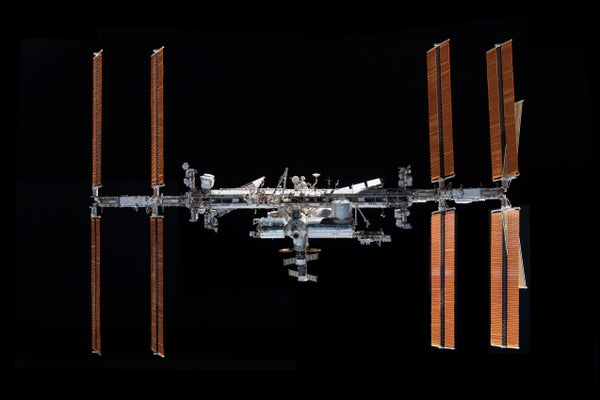

The ISS’s first modules reached orbit in 1998, and the station has been continuously crewed since 2000. But nothing lasts forever, not even the largest and most expensive piece of orbital infrastructure yet built by humankind. NASA has deemed the aging ISS too bulky and unwieldy to bring back to Earth intact or to boost into a higher, longer-lasting “graveyard” orbit. So the station’s end-of-life plan instead demands a carefully choreographed, fiery plunge into the atmosphere that will dump any lingering remains into an unpopulated stretch of ocean.

NASA announced in June that SpaceX would provide the means for the station’s destruction, currently set for early 2031, by designing and building a specialized deorbit vehicle based on its Dragon spacecraft. It wasn’t until a July 17 press conference, however, that the agency and company released additional details that revealed the scope of the changes SpaceX will make to undertake the daunting task. Although the company is looking to fly a standard, used Cargo Dragon capsule as part of the vehicle, this will be attached to a brand-new, supercharged trunk section that will be packed with rocket engines and tote extra propellant to execute the complicated, high-stakes maneuver.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“They’re calling it a bigger trunk, but it’s nothing like the little piece of carbon fiber that they use for a trunk now: it’s a much more sophisticated, complex spacecraft,” says Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian and an expert on spaceflight. “This is all old technology, yes, but you’re putting it together in a very new way.”

A typical SpaceX Cargo Dragon that visits the ISS is powered by 16 Draco engines. The deorbit vehicle will carry an additional 30 Draco engines inside its trunk, with between 22 and 26 firing at a time, to give the spacecraft the heft needed to wrangle the sprawling station. While Draco engines have been flying in space since 2010, however, the new arrangement has never been used before and will need to be thoroughly tested, McDowell says. (The company also produces a SuperDraco engine that can create about 200 times more thrust, but these are only used in the launch abort system of Crew Dragon vehicles.)

In addition to nearly tripling the number of engines of a typical Dragon, SpaceX’s plan calls for the deorbit vehicle to launch with some 16,000 kilograms (about 35,000 pounds) of propellant. That’s six times more than a standard Dragon, said Sarah Walker, director of Dragon mission management at SpaceX, during the press conference.

All those additions would make the deorbit vehicle far too heavy to blast off on SpaceX’s workhorse Falcon 9 rocket or other launchers in its class. Instead NASA—which has currently commissioned from SpaceX only the construction of the deorbit vehicle, not its launch or operations—will need to turn to a heavy launch vehicle. The company’s Falcon Heavy would be a clear front-runner for the job, McDowell says, noting that United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan, which first launched in January, or Blue Origin’s forthcoming New Glenn, scheduled to launch in September, may also be powerful enough to handle the hefty deorbit vehicle.

NASA has provided additional details about its choice to hire SpaceX for the job. The agency received three proposals in total but eliminated one that did not meet the essential requirements. The two proposals came from unsurprising sources, McDowell says: SpaceX, which operates both cargo and crew missions to the space station, and Northrop Grumman, which has conducted 20 supply runs to the station and plans to launch another next month. NASA’s evaluation showed that SpaceX’s proposal was less costly and more capable, however, according to a report by Ken Bowersox, associate administrator of NASA’s Space Operations Mission Directorate.

Despite the emphasis on integrating trusted existing technology into the deorbit vehicle, the fact remains that humans have never disposed of a spacecraft as big as the ISS, which stretches nearly the length of a football field, contains more interior space than a six-bedroom house and weighs some 460 tons. Its predecessor in controlled space-habitat deorbits, Russia’s Mir station, was far more compact and weighed less than one third as much.

When those final, fateful moments are at hand, the ISS and deorbit vehicle alike will be at the mercy of Earth’s thick atmosphere, which will buffet and burn away at the iconic facility. If the deorbit vehicle isn’t strong enough to maintain a smooth trajectory, the plummeting station could tumble through the skies, break apart and scatter dangerous debris across heavily populated swaths of Earth rather than dropping safely into the ocean. It will be perhaps SpaceX’s and Dragon’s highest-stakes mission to date after more than a decade of visits to the orbiting lab.

“It’s a wonderful full-circle experience,” Walker said at the press conference, “to go from being the first commercial vehicle to approach and attach to the space station all the way through when they’re ready to pass the baton to the next platforms that will come after.”